Concrete Masonry Basement Wall Construction

Introduction

Basements allow a building owner to significantly increase usable living, working, or storage space at a relatively low cost. Old perceptions of basements have proven outdated by stateofthe-art waterproofing, improved drainage systems, and natural lighting features such as window wells. Other potential benefits of basements include room for expansion of usable space, increased resale value, and safe haven during storms.

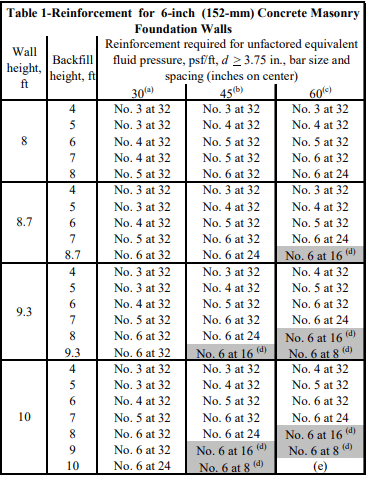

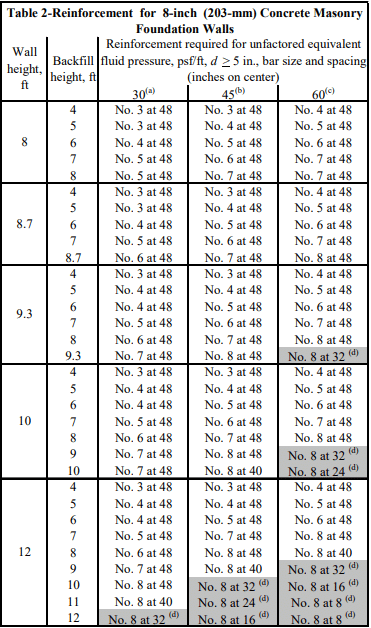

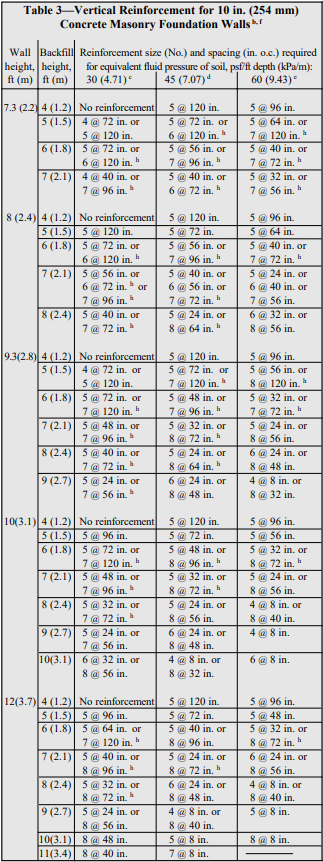

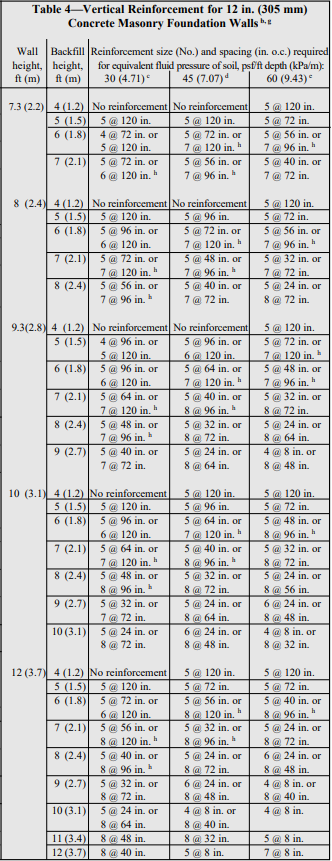

Historically, plain (unreinforced) concrete masonry walls have been used to effectively resist soil loads. Currently, however, reinforced walls are becoming more popular as a way to use thinner walls to resist large backfill pressures. Regardless of whether the wall is plain or reinforced, successful performance of a basement wall relies on quality construction in accordance with the structural design and the project specifications.

Materials

Concrete Masonry Units: Concrete masonry units should comply with Standard Specification for Loadbearing Concrete Masonry Units, ASTM C 90 (ref. 8). Specific colors and textures may be specified to provide a finished interior to the basement. Drywall can also be installed on furring strips, if desired. A rule of thumb for estimating the number of concrete masonry units to order is 113 units for every 100 ft2 (9.3 m2) of wall area. This estimate assumes the use of 3/8 in. (9.5 mm) mortar joints.

Mortar: Mortar serves several important functions in a concrete masonry wall; it bonds the units together, seals joints against air and moisture penetration, and bonds to joint reinforcement, ties, and anchors so that all components perform as a structural element.

Mortar should comply with Standard Specification for Mortar for Unit Masonry, ASTM C 270 (ref. 9). In addition, most building codes require the use of Type M or S mortar for construction of basement walls (refs. 2, 4, 5, 9, 13), because Type M and S mortars provide higher compressive strengths. Table 1 lists mortar proportions.

Typical concrete masonry construction uses about 8.5 ft3 (0.24 m3) of mortar for every 100 ft2 (9.3 m2) of masonry wall area. This figure assumes 3/8 in. (9.5 mm) thick mortar joints, face shell mortar bedding, and a 10% allowance for waste.

Grout: In reinforced concrete masonry construction, grout is used to bond the reinforcement and the masonry together. Grout should conform to Standard Specification for Grout for Masonry, ASTM C 476 (ref. 10), with the proportions listed in Table 2. As an alternative to complying with the proportion requirements in Table 2, grout can be specified to have a minimum compressive strength of 2000 psi (13.8 MPa) at 28 days. Enough water should be added to the grout so that it will have a slump of 8 to 11 in. (203 to 279 mm). The high slump allows the grout to be fluid enough to flow around reinforcing bars and into small voids. This initially high water-to-cement ratio is reduced significantly as the masonry units absorb excess mix water. Thus, grout gains high strengths despite the initially high waterto-cement ratio.

Construction

Prior to laying the first course of masonry, the top of the footing must be cleaned of mud, dirt, ice or other materials which reduce the bond between the mortar and the footing. This can usually be accomplished using brushes or brooms, although excessive oil or dirt may require sand blasting.

Masons typically lay the corners of a basement first so that alignment is easily maintained. This also allows the mason to plan where cuts are necessary for window openings or to fit the building’s plan.

To make up for surface irregularities in the footing, the first course of masonry is set on a mortar bed joint which can range from 1/4 to 3/4 in. (6.4 to 19 mm) in thickness. This initial bed joint should fully bed the first course of masonry units, although mortar should not excessively protrude into cells that will be grouted.

All other mortar joints should be approximately 3/8 in. (9.5 mm) thick and, except for partially grouted masonry, need only provide face shell bedding for the masonry units. In partially grouted construction, webs adjacent to the grouted cells are mortared to restrict grout from flowing into ungrouted cores. Head joints must be filled solidly for a thickness equal to a face shell thickness of the units.

Tooled concave joints provide the greatest resistance to water penetration. On the exterior face of the wall, mortar joints may be cut flush if parging coats are to be applied.

When joint reinforcement is used, it should be placed directly on the block with mortar placed over the reinforcement in the usual method. A mortar cover of at least 5/8 in. (15.9 mm) should be provided between the exterior face of the wall and the joint reinforcement. A mortar cover of 1/2 in. (12.7 mm) is needed on the interior face of the wall. For added safety against corrosion, hot dipped galvanized joint reinforcement is recommended.

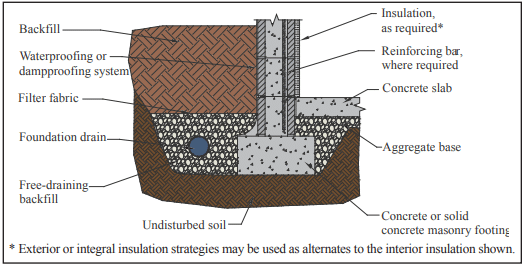

See Figures 1-4 for construction details.

Reinforced Masonry: For reinforced masonry construction, the reinforcing bars must be properly located to be fully functional. In most cases, vertical bars are positioned towards the interior face of basement walls to provide the greatest resistance to soil pressures. Bar positioners at the top and bottom of the wall prevent the bars from moving out of position during grouting. A space of at least 1/2 in. (12.7 mm) for coarse grout and 1/4 in. (6.4 mm) for fine grout should be maintained between the bar and the face shell of the block so that grout can flow completely around the reinforcing bars.

As mix water is absorbed by the units, voids can form in the grout. Accordingly, grout must be puddled or consolidated after placement to eliminate these voids and to increase the bond between the grout and the masonry units. Most codes permit puddling of grout when it is placed in lifts less than about 12 in. (305 mm). Lifts over 12 inches (305 mm) should be mechanically consolidated and then reconsolidated after about 3 to 10 minutes.

Surface Bonding: Another method of constructing concrete masonry walls is to dry stack units (without mortar) and then apply surface bonding mortar to both faces of the wall. The surface bonding mortar contains thousands of small glass fibers. When the mortar is applied properly to the required thickness, these fibers, along with the strength of the mortar itself, help produce walls of comparable strength to conventionally laid plain masonry walls. Surface bonded walls offer the benefits of excellent dampproof coatings on each face of the wall and ease of construction.

Dry-stacked walls should be laid in an initial full mortar bed to level the first course. Level coursing is maintained by using a rubbing stone to smooth small protrusions on the block surfaces and by inserting shims every two to four courses.

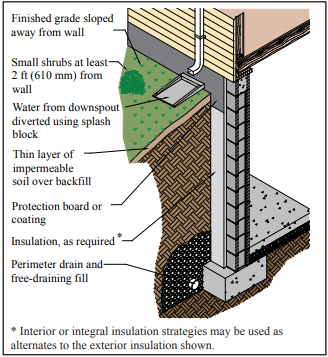

Water Penetration Resistance: Protecting below grade walls from water entry involves installation of a barrier to water and water vapor. An impervious barrier on the exterior wall surface can prevent moisture entry.

The barrier is part of a comprehensive system to prevent water penetration, which includes proper wall construction and the installation of drains, gutters, and proper grading.

Building codes (refs. 2, 4 , 5, 9, 13) typically require that basement walls be dampproofed for conditions where hydrostatic pressure will not occur, and waterproofed where hydrostatic pressures may exist. Dampproofing is appropriate where groundwater drainage is good, for example where granular backfill and a subsoil drainage system are present. Hydrostatic pressure may exist due to a high water table, or due to poorly draining backfill, such as heavy clay soils. Materials used for waterproofing are generally elastic, allowing them to span small cracks and accommodate minor movements.

When choosing a waterproof or dampproof system, consideration should be given to the degree of resistance to hydrostatic head of water, absorption characteristics, elasticity, stability in moist soil, resistance to mildew and algae, impact or puncture resistance, and abrasion resistance. A complete discussion of waterproofing, dampproofing, and drainage systems is included in TEK 19-03A (ref. 6).

All dampproofing and waterproofing systems should be applied to walls that are clean and free from dirt, mud and other materials which may reduce bond between the coating and the concrete masonry wall.

Draining water away from basement walls significantly reduces the pressure the walls must resist and reduces the possibility of water infiltration into the basement if the waterproofing (or dampproofing) system fails. Perforated pipe has historically proven satisfactory when properly installed. When placed on the exterior side of basement walls, perforated pipes are usually laid in crushed stone to facilitate drainage. To prevent migration of fine soil into the drains, filter fabrics are often placed over the gravel.

Drainage pipes can also be placed beneath the slab and connected into a sump. Pipes through the footing or the wall drain water from the exterior side of the basement wall.

The drainage and waterproofing systems should always be inspected prior to backfilling to ensure they are adequately placed. Any questionable workmanship or materials should be repaired at this stage since repairs are difficult and expensive after backfilling.

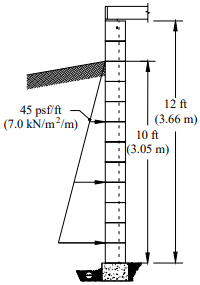

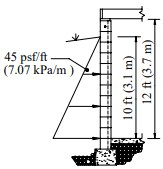

Backfilling: One of the most crucial aspects of basement construction is how and when to properly backfill. Walls should be properly braced or have the first floor in place prior to backfilling. Otherwise, a wall which is designed to be supported at the top may crack or even fail from the large soil pressures. Figure 5 shows one bracing scheme which has been widely used for residential basement walls. More substantial bracing may be required for high walls or large backfill pressures.

The backfill material should be free-draining soil without large stones, construction debris, organic materials, and frozen earth. Saturated soils, especially saturated clays, should generally not be used as backfill materials since wet materials significantly increase the hydrostatic pressure on the walls.

Backfill materials should be placed in several lifts and each layer should be compacted with small mechanical tampers. Care should be taken when placing the backfill materials to avoid damaging the drainage, waterproofing or exterior insulation systems. Sliding boulders and soil down steep slopes should thus be avoided since the high impact loads generated can damage not only the drainage and waterproofing systems but the wall as well. Likewise, heavy equipment should not be operated within about 3 feet (0.9 m) of any basement wall system.

The top 4 to 8 in. (102 to 203 mm) of backfill materials should be low permeability soil so rain water is absorbed into the backfill slowly. Grade should be sloped away from the basement at least 6 in. (152 mm) within 10 feet (3.1 m) of the building. If the ground naturally slopes toward the building, a shallow swale can be installed to redirect runoff.

Construction Tolerances

Specifications for Masonry Structures (ref. 8) specifies tolerances for concrete masonry construction. These tolerances were developed to avoid structurally impairing a wall because of improper placement.

- Dimension of elements in cross section or elevation

…………………………………….¼ in. (6.4 mm), +½ in. (12.7 mm) - Mortar joint thickness: bed………………………..+⅛ in. (3.2 mm)

head………………………………..-¼ in (6.4 mm), +⅜ in. (9.5 mm) - Elements

- Variation from level: bed joints……………………………………….

±¼ in. (6.4 mm) in 10 ft (3.1 m), ±½ in. (12.7 mm) max

top surface of bearing walls……………………………………………..

±¼ in.(6.4 mm), +⅜ in.(9.5 mm), ±½ in.(12.7mm) max - Variation from plumb………….±¼ in. (6.4 mm) 10 ft (3.1 m)

………………………………………±⅜ in. (9.5 mm) in 20 ft (6.1 m)

……………………………………………±½ in. (12.7 mm) maximum - True to a line…………………..±¼ in. (6.4 mm) in 10 ft (3.1 m)

………………………………………±⅜ in. (9.5 mm) in 20 ft (6.1 m)

……………………………………………±½ in. (12.7 mm) maximum - Alignment of columns and bearing walls (bottom versus top)

……………………………………………………………..±½ in (12.7 mm)

- Variation from level: bed joints……………………………………….

- Location of elements

- Indicated in plan……………..±½ in (12.7 mm) in 20 ft (6.1 m)

…………………………………………….±¾ in. (19.1 mm) maximum - Indicated in elevation

……………………………………….±¼ in. (6.4 mm) in story height

…………………………………………….±¾ in. (19.1 mm) maximum

- Indicated in plan……………..±½ in (12.7 mm) in 20 ft (6.1 m)

Insulation: The thermal performance of a masonry wall depends on its R-value as well as the thermal mass of the wall. Rvalue describes the ability to resist heat flow; higher R-values give better insulating performance. The R-value is determined by the size and type of masonry unit, type and amount of insulation, and finish materials. Depending on the particular site conditions and owner’s preference, insulation may be placed on the outside of block walls, in the cores of hollow units, or on the interior of the walls.

Thermal mass describes the ability of materials like concrete masonry to store heat. Masonry walls remain warm or cool long after the heat or air-conditioning has shut off, keeping the interior comfortable. Thermal mass is most effective when insulation is placed on the exterior or in the cores of the block, where the masonry is in direct contact with the interior conditioned air.

Exterior insulated masonry walls typically use rigid board insulation adhered to the soil side of the wall. The insulation requires a protective finish where it is exposed above grade to maintain durability, integrity, and effectiveness.

Concrete masonry cores may be insulated with molded polystyrene inserts, expanded perlite or vermiculite granular fills, or foamed-in-place insulation. Inserts may be placed in the cores of conventional masonry units, or they may be used in block specifically designed to provide higher R-values.

Interior insulation typically consists of insulation installed between furring strips, finished with gypsum wall board or panelling. The insulation may be fibrous batt, rigid board, or fibrous blown-in insulation.

Design Features

Interior Finishes: Split faced, scored, burnished, and fluted block give owners and designers added options to standard block surfaces. Colored units can be used in the entire wall or in sections to achieve specific patterns.

Although construction with staggered vertical mortar joints (running bond) is standard for basement construction, the appearance of continuous vertical mortar joints (stacked bond pattern) can be achieved by using of scored units or reinforced masonry construction.

Natural Lighting: Because of the modular nature of concrete masonry, windows and window wells of a variety of shapes and sizes can be easily accommodated, giving basements warm, natural lighting. For additional protection and privacy, glass blocks can be incorporated in lieu of traditional glass windows.

References

- Basement Manual-Design and Construction Using Concrete Masonry, CMU-MAN-002-01, Concrete Masonry & Hardscapes Association, 2001.

- BOCA National Building Code. Country Club Hills, IL: Building Officials and Code Administrators International, Inc. (BOCA), 1999.

- Building Code Requirements for Masonry Structures, ACI 530-02/ASCE 5-02/TMS 402-02. Reported by the Masonry Standards Joint Committee, 2002.

- International Residential Code. Falls Church, VA: International Code Council, 2000.

- International Building Code. Falls Church, VA: International Code Council, 2000.

- Preventing Water Penetration in Below-Grade Concrete Masonry Walls, TEK 19-03A. Concrete Masonry & Hardscapes Association, 2001.

- Seismic Design Provisions for Masonry Structures, TEK 14-18B, Concrete Masonry & Hardscapes Association, 2009.

- Specifications for Masonry Structures, ACI 530.1-02/ASCE 6-99/TMS 602-02. Reported by the Masonry Standards Joint Committee, 2002.

- Standard Building Code. Birmingham, AL: Southern Building Code Congress International, Inc. (SBCCI), 1999.

- Standard Specification for Grout for Masonry, ASTM C 476-01. American Society for Testing and Materials, 2001.

- Standard Specification for Load-Bearing Concrete Masonry Units, ASTM C 90-01. American Society for Testing and Materials, 2001.

- Standard Specification for Mortar for Unit Masonry, ASTM C 270-00. American Society for Testing and Materials, 2000.

- Uniform Building Code. Whittier, CA: International Conference of Building Officials (ICBO), 1997.

tek-03-11,tek 03 11,03-11,3-11,3 11