Grouting Concrete Masonry Walls

INTRODUCTION

Grouted concrete masonry construction offers design flexibility through the use of partially or fully grouted walls, whether plain or reinforced. The industry is experiencing fast-paced advances in grouting procedures and materials as building codes allow new opportunities to explore means and methods for constructing grouted masonry walls.

Grout is a mixture of: cementitious material (usually portland cement); aggregate; enough water to cause the mixture to flow readily and without segregation into cores or cavities in the masonry; and sometimes admixtures. Grout is used to give added strength to both reinforced and unreinforced concrete masonry walls by grouting either some or all of the cores. It is also used to fill bond beams and occasionally to fill the collar joint of a multi-wythe wall. Grout may also be added to increase the wall’s fire rating, acoustic effectiveness termite resistance, blast resistance, heat capacity or anchorage capabilities. Grout may also be used to stabilize screen walls and other landscape elements.

In reinforced masonry, grout bonds the masonry units and reinforcing steel so that they act together to resist imposed loads. In partially grouted walls, grout is placed only in wall spaces containing steel reinforcement. When all cores, with or without reinforcement, are grouted, the wall is considered solidly grouted. If vertical reinforcement is spaced close together and/or there are a significant number of bond beams within the wall, it may be faster and more economical to solidly grout the wall.

Specifications for grout, sampling and testing procedures, and information on admixtures are covered in CMHA TEK 09-04A, Grout for Concrete Masonry (ref. 1). This TEK covers methods for laying the units, placing steel reinforcement and grouting.

WALL CONSTRUCTION

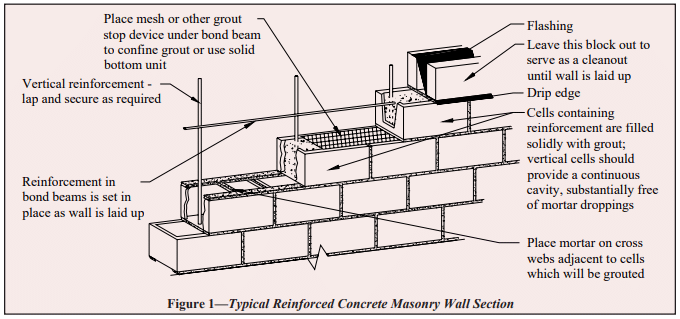

Figure 1 shows the basic components of a typical reinforced concrete masonry wall. When walls will be grouted, concrete masonry units must be laid up so that vertical cores are aligned to form an unobstructed, continuous series of vertical spaces within the wall.

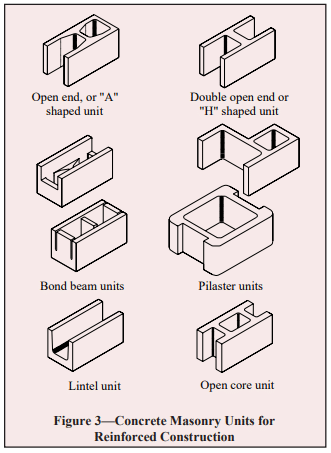

Head and bed joints must be filled with mortar for the full thickness of the face shell. If the wall will be partially grouted, those webs adjacent to the cores to be grouted are mortared to confine the grout flow. If the wall will be solidly grouted, the cross webs need not be mortared since the grout flows laterally, filling all spaces. In certain instances, full head joint mortaring should also be considered when solid grouting since it is unlikely that grout will fill the space between head joints that are only mortared the width of the face shell, i.e., when penetration resistance is a concern such as storm shelters and prison walls. In cases such as those, open end or open core units (see Figure 3) should be considered as there is no space between end webs with these types of units.

Care should be taken to prevent excess mortar from extruding into the grout space. Mortar that projects more than ½ in. (13 mm) into the grout space must be removed (ref. 3). This is because large protrusions can restrict the flow of grout, which will tend to bridge at these locations potentially causing incomplete filling of the grout space. To prevent bridging, grout slump is required to be between 8 and 11 in. (203 to 279 mm) (refs. 2, 3) at the time of placement. This slump may be adjusted under certain conditions such as hot or cold weather installation, low absorption units or other project specific conditions. Approval should be obtained before adjusting the slump outside the requirements. Using the grout demonstration panel option in Specification for Masonry Structures (ref. 3) is an excellent way to demonstrate the acceptability of an alternate grout slump. See the Grout Demonstration Panel section of this TEK for further information.

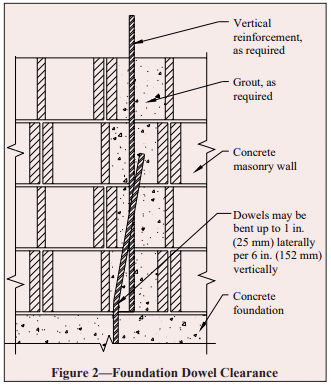

At the footing, mortar bedding under the first course of block to be grouted should permit grout to come into direct contact with the foundation or bearing surface. If foundation dowels are present, they should align with the cores of the masonry units. If a dowel interferes with the placement of the units, it may be bent a maximum of 1 in. (25 mm) horizontally for every 6 in. (152 mm) vertically (see Figure 2). When walls will be solidly grouted, saw cutting or chipping away a portion of the web to better accommodate the dowel may also be acceptable. If there is a substantial dowel alignment problem, the project engineer must be notified.

Vertical reinforcing steel may be placed before the blocks are laid, or after laying is completed. If reinforcement is placed prior to laying block, the use of open-end A or H- shaped units will allow the units to be easily placed around the reinforcing steel (see Figure 3). When reinforcement is placed after wall erection, reinforcing steel positioners or other adequate devices to hold the reinforcement in place are commonly used, but not required. However, it is required that both horizontal and vertical reinforcement be located within tolerances and secured to prevent displacement during grouting (ref. 3). Laps are made at the end of grout pours and any time the bar has to be spliced. The length of lap splices should be shown on the project drawings. On occasion there may be locations in the structure where splices are prohibited. Those locations are to be clearly marked on the drawing.

Reinforcement can be spliced by either contact or noncontact splices. Noncontact lap splices may be spaced as far apart as one-fifth the required length of the lap but not more than 8 in. (203 mm) per Building Code Requirements for Masonry Structures (ref. 4). This provision accommodates construction interference during installation as well as misplaced dowels. Splices are not required to be tied, however tying is often used as a means to hold bars in place.

As the wall is constructed, horizontal reinforcement can be placed in bond beam or lintel units. If the wall will not be solidly grouted, the grout may be confined within the desired grout area either by using solid bottom masonry bond beam units or by placing plastic or metal screening, expanded metal lath or other approved material in the horizontal bed joint before laying the mortar and units being used to construct the bond beam. Roofing felt or materials that break the bond between the masonry units and mortar should not be used for grout stops.

CONCRETE MASONRY UNITS AND REINFORCING BARS

Standard two-core concrete masonry units can be effectively reinforced when lap splices are not long, since the mason must lift the units over any vertical reinforcing bars that extend above the previously installed masonry. The concrete masonry units illustrated in Figure 3 are examples of shapes that have been developed specifically to accommodate reinforcement. Open-ended units allow the units to be placed around reinforcing bars. This eliminates the need to thread units over the top of the reinforcing bar. Horizontal reinforcement in concrete masonry walls can be accommodated either by saw-cutting webs out of a standard unit or by using bond beam units. Bond beam units are manufactured with either reduced webs or with “knock-out” webs, which are removed prior to placement in the wall. Pilaster and column units are used to accommodate a wall- column or wall-pilaster interface, allowing space for vertical reinforcement and ties, if necessary, in the hollow center.

Concrete masonry units should meet applicable ASTM standards and should typically be stored on pallets to prevent excessive dirt and water from contaminating the units. The units may also need to be covered to protect them from rain and snow.

The primary structural reinforcement used in concrete masonry is deformed steel bars. Reinforcing bars must be of the specified diameter, type and grade to assure compliance with the contract documents. See Steel Reinforcement for Concrete Masonry, TEK 12-04D for more information (ref. 6). Shop drawings may be required before installation can begin.

Light rust, mill scale or a combination of both need not be removed from the reinforcement. Mud, oil, heavy rust and other materials which adversely affect bond must be removed however. The dimensions and weights (including heights of deformations) of a cleaned bar cannot be less than those required by the ASTM specification.

GROUT PLACEMENT

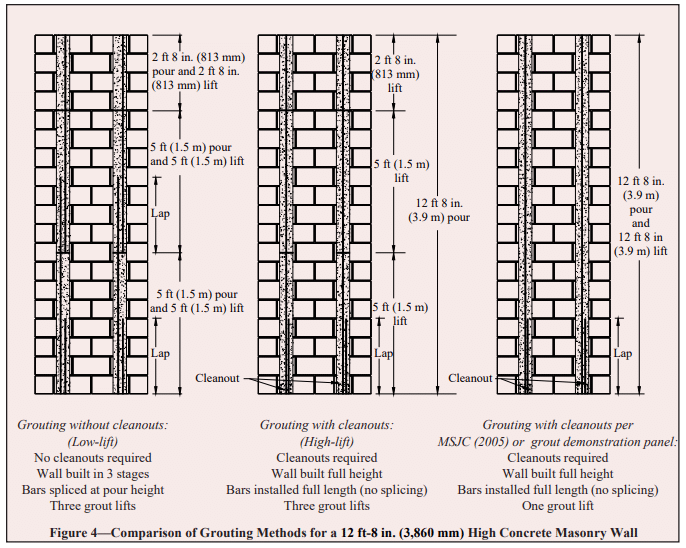

To understand grout placement, the difference between a grout lift and a grout pour needs to be understood. A lift is the amount of grout placed in a single continuous operation. A pour is the entire height of masonry to be grouted prior to the construction of additional masonry. A pour may be composed of one lift or a number of successively placed grout lifts, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Historically, only two grout placement procedures have been in general use: (l) where the wall is constructed to pour heights up to 5 ft (1,520 mm) without cleanouts—generally termed “low lift grouting;” and (2) where the wall is constructed to a maximum pour height of 24 ft (7,320 mm) with required cleanouts and lifts are placed in increments of 5 ft (1,520 mm)—generally termed “high lift grouting.” With the advent of the 2002 Specification for Masonry Structures (ref. 5), a third option became available – grout demonstration panels. The 2005 Specification for Masonry Structures (ref. 3) offers an additional option: to increase the grout lift height to 12 ft-8 in. (3,860 mm) under the following conditions:

- the masonry has cured for at least 4 hours,

- grout slump is maintained between 10 and 11 in. (245 and 279 mm), and

- no intermediate reinforced bond beams are placed between the top and the bottom of the pour height.

Through the use of a grout demonstration panel, lift heights in excess of the 12 ft-8 in. (3,860 mm) limitation may be permitted if the results of the demonstration show that the completed grout installation is not adversely affected. Written approval is also required.

These advances permit more efficient installation and construction options for grouted concrete masonry walls (see Figure 4).

Grouting Without Cleanouts—”Low-Lift Grouting”

Grout installation without cleanouts is sometimes called low-lift grouting. While the term is not found in codes or standards, it is common industry language to describe the process of constructing walls in shorter segments, without the requirements for cleanout openings, special concrete block shapes or equipment. The wall is built to scaffold height or to a bond beam course, to a maximum of 5 ft (1,520 mm). Steel reinforcing bars and other embedded items are then placed in the designated locations and the cells are grouted. Although not a code requirement, it is considered good practice (for all lifts except the final) to stop the level of the grout being placed approximately 1 in. (25 mm) below the top bed joint to help provide some mechanical keying action and water penetration resistance. Further, this is needed only when a cold joint is formed between the lifts and only in areas that will be receiving additional grout. Steel reinforcement should project above the top of the pour for sufficient height to provide for the minimum required lap splice, except at the top of the finished wall.

Grout is to be placed within 1 ½ hours from the initial introduction of water and prior to initial set (ref. 3). Care should be taken to minimize grout splatter on reinforcement, on finished masonry unit faces or into cores not immediately being grouted. Small amounts of grout can be placed by hand with buckets. Larger quantities should be placed by grout pumps, grout buckets equipped with chutes or other mechanical means designed to move large volumes of grout without segregation.

Grout must be consolidated either by vibration or puddling immediately after placement to help ensure complete filling of the grout space. Puddling is allowed for grout pours of 12 in. (305 mm) or less. For higher pour heights, mechanical vibration is required and reconsolidation is also required. See the section titled Consolidation and Reconsolidation in this TEK.

Grouting With Cleanouts—”High-Lift Grouting”

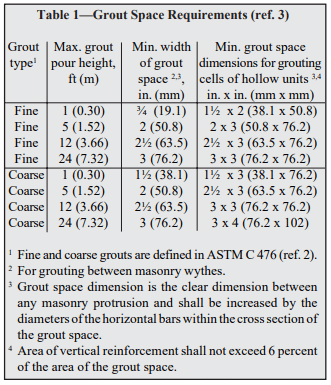

Many times it is advantageous to build the masonry wall to full height before grouting rather than building it in 5 ft (1,520 mm) increments as described above. With the installation of cleanouts this can be done. Typically called high-lift grouting within the industry, grouting with cleanouts permits the wall to be laid up to story height or to the maximum pour height shown in Table 1 prior to the installation of reinforcement and grout. (Note that in Table 1, the maximum area of vertical reinforcement does not include the area at lap splices.) High lift grouting offers certain advantages, especially on larger projects. One advantage is that a larger volume of grout can be placed at one time, thereby increasing the overall speed of construction. A second advantage is that high-lift grouting can permit constructing masonry to the full story height before placing vertical reinforcement and grout. Less reinforcement is used for splices and the location of the reinforcement can be easily checked by the inspector prior to grouting. Bracing may be required during construction. See Bracing Concrete Masonry Walls During Construction, TEK 03-04C (ref. 7) for further information.

Cleanout openings must be made in the face shells of the bottom course of units at the location of the grout pour. The openings must be large enough to allow debris to be removed from the space to be grouted. For example, Specification for Masonry Structures (ref. 3) requires a minimum opening dimension of 3 in. (76 mm).

Cleanouts must be located at the bottom of all cores containing dowels or vertical reinforcement and at a maximum of 32 in. (813 mm) on center (horizontal measurement) for solidly grouted walls. Face shells are removed either by cutting or use of special scored units which permit easy removal of part of the face shell for cleanout openings (see Figure 5). When the cleanout opening is to be exposed in the finished wall, it may be desirable to remove the entire face shell of the unit, so that it may be replaced in whole to better conceal the opening. At flashing where reduced thickness units are used as shown in Figure 1, the exterior unit can be left out until after the masonry wall is laid up. Then after cleaning the cell, the unit is mortared in which allowed enough time to gain enough strength to prevent blowout prior to placing the grout.

Proper preparation of the grout space before grouting is very important. After laying masonry units, mortar droppings and projections larger than ½ in. (13 mm) must be removed from the masonry walls, reinforcement and foundation or bearing surface. Debris may be removed using an air hose or by sweeping out through the cleanouts.

The grout spaces should be checked by the inspector for cleanliness and reinforcement position before the cleanouts are closed. Cleanout openings may be sealed by mortaring the original face shell or section of face shell, or by blocking the openings to allow grouting to the finish plane of the wall. Face shell plugs should be adequately braced to resist fluid grout pressure.

It may be advisable to delay grouting until the mortar has been allowed to cure, in order to prevent horizontal movement (blowout) of the wall during grouting. When using the increased grout lift height provided for in Article 3.5 D of Specification for Masonry Structures (ref 3), the masonry is required to cure for a minimum of 4 hours prior to grouting for this reason.

Consolidation and Reconsolidation

An important factor mentioned in both grouting procedures is consolidation. Consolidation eliminates voids, helping to ensure complete grout fill and good bond in the masonry system.

As the water from the grout mixture is absorbed into the masonry, small voids may form and the grout column may settle. Reconsolidation acts to remove these small voids and should generally be done between 3 and 10 minutes after grout placement. The timing depends on the water absorption rate, which varies with such factors as temperature, absorptive properties of the masonry units and the presence of water repellent admixtures in the units. It is important to reconsolidate after the initial absorption has taken place and before the grout loses its plasticity. If conditions permit and grout pours are so timed, consolidation of a lift and reconsolidation of the lift below may be done at the same time by extending the vibrator through the top lift and into the one below. The top lift is reconsolidated after the required waiting period and then filled with grout to replace any void left by settlement.

A mechanical vibrator is normally used for consolidation and reconsolidation—generally low velocity with a ¾ in. to 1 in. (19 to 25 mm) head. This “pencil head” vibrator is activated for a few seconds in each grouted cell. Although not addressed by the code, recent research (ref. 8) has demonstrated adequate consolidation by vibrating the top 8 ft (2,440 mm) of a grout lift, relying on head pressure to consolidate the grout below. The vibrator should be withdrawn slowly enough while on to allow the grout to close up the space that was occupied by the vibrator. When double open- end units are used, one cell is considered to be formed by the two open ends placed together. When grouting between wythes, the vibrator is placed at points spaced 12 to 16 in. (305 to 406 mm) apart. Excess vibration may blow out the face shells or may separate wythes when grouting between wythes and can also cause grout segregation.

GROUT DEMONSTRATION PANEL

Specification for Masonry Structures (ref. 3) contains a provision for “alternate grout placement” procedures when means and methods other than those prescribed in the document are proposed. The most common of these include increases in lift height, reduced or increased grout slumps, minimization of reconsolidation, puddling and innovative consolidation techniques. Grout demonstration panels have been used to allow placement of a significant amount of a relatively new product called self-consolidating grout to be used in many parts of the country with outstanding results.

Research has demonstrated comparable or superior performance when compared with consolidated and reconsolidated conventional grout in regard to reduction of voids, compressive strength and bond to masonry face shells. Construction and approval of a grout demonstration panel using the proposed grouting procedures, construction techniques and grout space geometry is required. With the advent of self-consolidating grouts and other innovative consolidation techniques, this provision of the Specification has been very useful in demonstrating the effectiveness of alternate grouting procedures to the architect/engineer and building official.

COLD WEATHER PROTECTION

Protection is required when the minimum daily temperature during construction of grouted masonry is o o expected to fall below 40 F (4.4 C). Grouted masonry requires special consideration because of the higher water content and potential disruptive expansion that can occur if that water freezes. Therefore, grouted masonry requires protection for longer periods than ungrouted masonry to allow the water to dissipate. For more detailed information on cold, hot, and wet weather protection, see All-Weather Concrete Masonry Construction, TEK 03-01C (ref. 9).

REFERENCES

- Grout for Concrete Masonry, TEK 09-04A. Concrete Masonry & Hardscapes Association, 2005.

- Standard Specification for Grout for Masonry, ASTM C 476-02, ASTM International, 2005.

- Specification for Masonry Structures, ACI 530.1-05/ ASCE 6-05/TMS 602-05. Reported by the Masonry Standards Joint Committee, 2005.

- Building Code Requirements for Masonry Structures, ACI 530-05/ASCE 5-05/TMS 402-05. Reported by the Masonry Standards Joint Committee, 2005.

- Specification for Masonry Structures, ACI 530.1-02/ ASCE 6-02/TMS 602-02. Reported by the Masonry Standards Joint Committee, 2002.