Flashing Strategies for Concrete Masonry Walls

INTRODUCTION

The primary role of flashing is to intercept the flow of moisture through masonry and direct it to the exterior of the structure. Due to the abundant sources of moisture and the potentially detrimental effects it can have, the choice of flashing material, and the design and construction of flashing details, can often be as key to the performance of a masonry structure as that of the structural system.

The type of flashing material to be used is governed by both environmental and design/build considerations. Environmental considerations include such factors as the physical state of moisture present (liquid, solid, or vapor), air movement, and temperature extremes as well as temperature differentials. Design/build considerations include the selection of the proper type of flashing material, location of the flashing, structural, and installation details. Drawings for flashing details, often the only method of communicating the necessary information between the designer and contractor, should be comprehensive and show sufficient detail for the proper interpretation and installation of flashing systems. TEK 19-05A Flashing Details for Concrete Masonry Walls (ref. 3) includes such details.

Although flashing is the primary focus of this TEK, it should be understood that the role of vapor retarders, air barriers, and insulation are also important elements to consider for any wall design as the performance of the entire system can be dependent on the design of its individual components.

EFFECT OF MOISTURE ON MASONRY

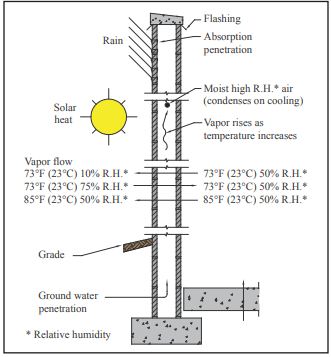

The damage caused to a masonry structure (or its contents) due to the infiltration of moisture can take many forms, depending on the source and the physical state of the water. For example, in the liquid state, water penetrating to the interior of a building may cause considerable damage to its contents. In some extreme cases, water trapped within the masonry may freeze, inducing spalling and cracking of the masonry units or mortar. Alternatively, water vapor can lead to condensation inside the cores and on the surfaces of masonry if the dew point temperature is reached. During cold weather, below 28 °F (-2 °C), water vapor can accumulate on a cold surface and form frost or increase the quantity of ice within the masonry.

Although it is commonly thought that moisture problems stem only from the external environment, this is not always the case. For example, in some instances it is possible for the humidity of interior air to cause water damage to the exterior of a structure. This damage may appear in the form of water stains, ravelled mortar joints, spalled surfaces, or efflorescence.

DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS

Water Movement

In the design of any structure, the presence and movement of water in any of its three forms needs to be considered. Significant forces that influence water movement include wind pressure, gravity, and moisture absorption by the material. Dynamic wind pressure on the surface of an exposed wall can drive exterior moisture (in the form of rain or irrigation water) into the masonry. Gravity, which is always present, draws the free water vertically downward, while the absorptive characteristics of the masonry can cause moisture migration in any direction by capillary action.

It should also be recognized that these forces do not act independently of one another. For example, wind-driven rain may enter masonry through cracks at the interface between mortar and units and migrate downward through the wall due to the force of gravity, or it may be transferred horizontally through the wall either by pressure or by flowing across the webs of the units or mortar bridges. Wind-driven rain can also be absorbed by masonry units and carried from the exterior surface to the interior surface by capillary action. Additionally, ground water may be drawn upward by the wicking action of units placed on porous foundations or by contact with moist soil.

Designers should never assume that any material is capable of rendering a wall totally impervious to water penetration. Surface treatments, designed to reduce the quantity of water entering a masonry structure, are helpful in this regard but should not be considered as a sole means of protection. Available as clear and opaque compounds, the effectiveness of surface treatments depends on their composition and compatibility with the masonry. They also do not reduce the movement by capillary action (wicking) of any water that does penetrate the masonry face through cracks or defects in the mortar/masonry.

The use of integral water repellent admixtures in concrete masonry units and mortars can also reduce the amount of water entering the masonry. In addition, they inhibit water penetrating the masonry face from wicking to the back face of the wall.

Proper selection and application of surface treatments and integral water repellents can greatly enhance the water resistant properties of masonry, but they should not be considered as substitutes for flashing. See TEKs 19-01 and 19-02B (refs. 8 and 2) for more information on water repellents for concrete masonry.

Flashing Location

The proper design of masonry for resistance to water penetration includes consideration of the various types of wall construction such as single wythe, cavity, veneer, etc. During the design phase it should be understood that all exterior masonry walls may be subjected to some degree of water penetration and/or water vapor movement during its design life. Flashing is recommended for all locations where moisture may potentially penetrate into a wall and where the free drainage of water is blocked. Some of these critical locations include the top of walls and parapets, at all horizontal obstructions such as over openings, beneath sills, above shelf angles, at the base of walls, and in walls at ground level to serve as a moisture retarder to reduce the amount of water wicked up into the masonry above grade.

When selecting the flashing material for a particular application, the service conditions, projected life of the structure, and past performance characteristics of the flashing materials should be reviewed. Flashing should be designed to perform satisfactorily for the design life of the building since repair or replacement can be very labor intensive and expensive.

FLASHING MATERIALS

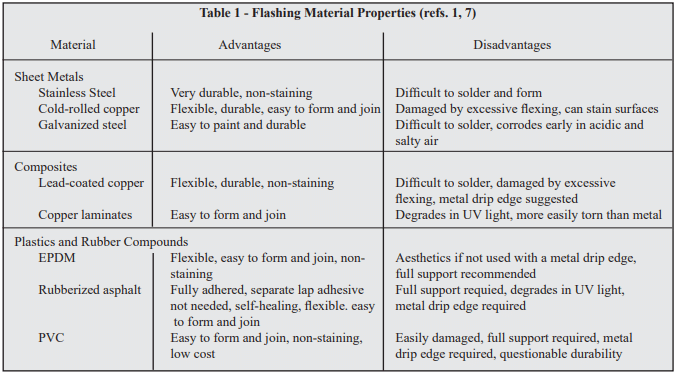

A wide variety of flashing materials are available. The selection of the type of flashing material to use can be influenced by several factors including cost, durability, compatibility with other materials, ease of installation, aesthetic value, and performance. Table 1 summarizes some of the attributes for various flashing materials. The advantages and disadvantages of each must be weighed for each individual project to provide the most cost-effective and desirable choice.

Prefabricated flashing boots may be available for inside and outside corners and end dams. These boots eliminate the need for cutting, folding, or tucking the flashing materials at these locations. However, due to construction tolerances, some of these prefabricated items, particularly those of rigid materials, may be difficult to fit into their intended location.

Sheet Metals

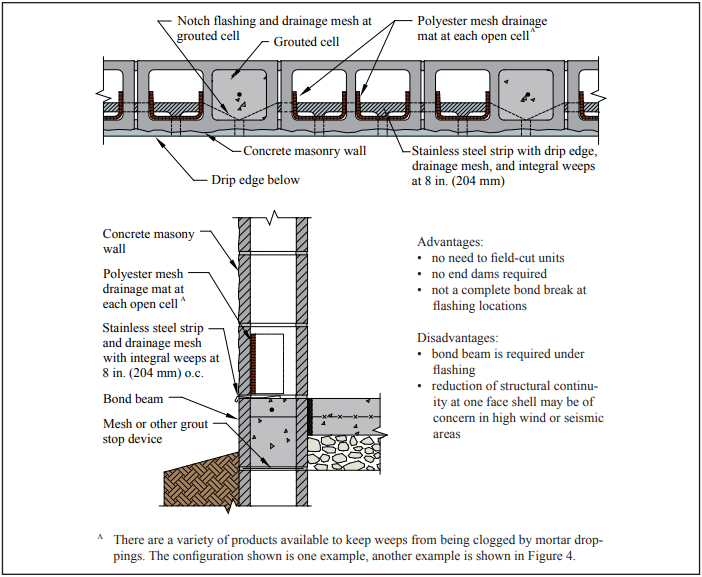

Stainless steel is technically any of a large and complex group of corrosion resistant iron chromium alloys possessing excellent weather and chemical resisting properties. Preformed sections must be properly sized so that on site modification is minimized. Stainless steel flashing with a conventional annealed finish should comply with Standard Specification for Stainless and Heat-Resisting Chromium-Nickel Steel Plate, Sheet, and Strip, ASTM A 167 (ref. 6). Generally, Type 304 stainless steel with a minimum thickness of 0.010 in. (0.25 mm) is satisfactory. Lap sections require solder conforming to Standard Specification for Solder Metal, ASTM B 32 (60% tin and 40% lead) (ref. 5). Stainless steel drip edges used in combination with other flashing materials offer an economical compromise with a durable drip edge.

Copper is a nonferrous metal possessing good ductility and malleability characteristics. Like stainless steel, it also possesses excellent weather and chemical resistant properties. Preformed sections or sheet materials are easily modified to conform to site requirements. However, it should be cautioned that once weathered, copper flashings produce a green patina that may impart a green stain to adjacent masonry surfaces that some find objectionable.

Galvanized steel is less expensive than stainless steel but is subject to corrosive attack from salts and acids. The galvanized coating also may crack at bends, lowering the corrosion resistance. As with stainless steel, it is also difficult to form and to solder laps effectively.

Composites

Combinations of metals and plastics are supplied by some dealers. The composition and application of these combined materials should be determined before use. Composites utilizing copper are the most popular since they combine the durability and malleability of copper with the nonstaining characteristics of a protective coating. Composites containing aluminum should be avoided.

Plastics and Rubber Compounds

Plastics are categorized as polymeric materials of large molecular weight, usually polyvinyl chloride (PVC) or polyethylene. Manufacturers of plastic flashings should be consulted for documentation establishing the longevity of the plastic in a caustic environment (pH = 12.5 to 13.5), the composition of the plastic, ease of working at temperatures ranging from 20 to 100 °F (-7 to 38 °C), and ability to withstand exposure to ultraviolet light.

Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer (EPDM) is a synthetic rubber that is used as a single ply roofing membrane as well as flashing. It has better low temperature performance than PVC and will not embrittle. It offers ultraviolet light and ozone resistance and can be left exposed.

Self-adhering, rubberized asphalt membranes consist of a composite of flexible plastic film for puncture and tear resistance combined with a rubberized asphalt adhesive layer. This material adheres to itself, requiring less effort to seal laps or corners which speeds installation. It also self-adheres to the substrate which prevents water from migrating under the flashing and is self-healing in the event of punctures. However, it should not be applied to damp, dirty, or dusty surfaces and typically has a lower installation temperature limit of 25 °F (-4 °C). Because it degrades in the presence of extended UV exposure, it should not be left exposed and requires a metal drip edge.

CONSTRUCTION PRACTICES

To perform, flashing must be designed and installed properly or it may aggravate rather than reduce water problems. Flashing should be longitudinally continuous or terminated with end dams. Longitudinally continuous requires that joints be overlapped sufficiently, 4 in. (102 mm) minimum, to prevent moisture from entering between the joints and they must be bonded (joined) together with adhesive if they are not self adhering to prevent water movement through the lap area. With metal flashings a ¼ in. (6.4 mm) gap joined and sealed with a pliable membrane helps in accommodating expansion (ref. 3).

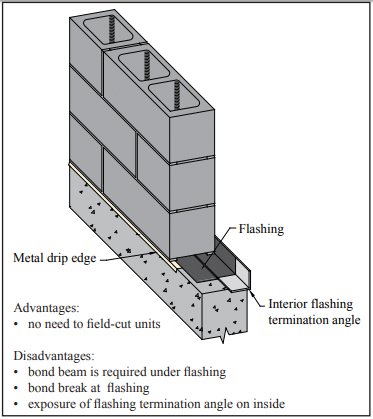

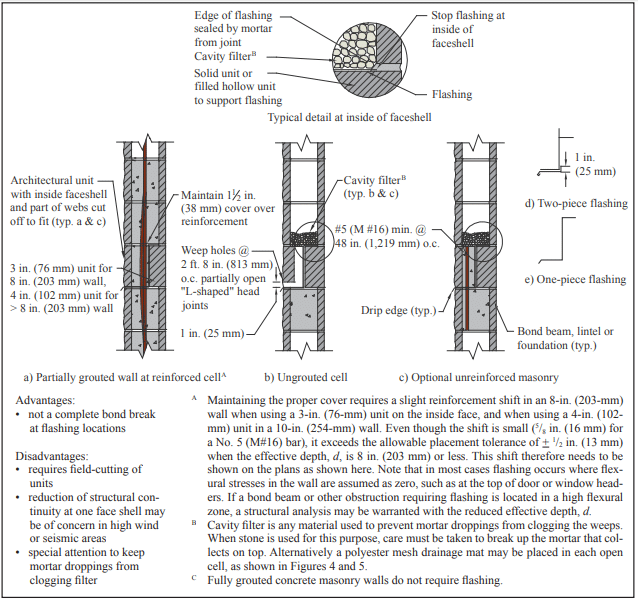

Flashings should be secured at the top by embedment into the masonry, a reglet, or should be adhesively attached so that water cannot infiltrate or move behind the attachment. For multi-wythe construction, the flashing should project downward along the outer surface of the inner wythe and then project outward at the masonry joint, shelf angle, or lintel where it is to discharge the water. Every effort should be made to slope the flashing towards the exterior. Effectively placed mortar or sealant material can help promote this drainage. The flashing should continue beyond the exterior face of the masonry a minimum of ¼ in. (6.4 mm) and terminate with a sloped drip edge.

An additional design consideration for flashings includes ensuring that all materials are compatible. For example, contact between dissimilar metals can result in the corrosion of one or both of the metals. Additionally, the coefficients of thermal expansion for the flashing and masonry materials differ. All flashing details should be designed to accommodate the resulting differential movement.

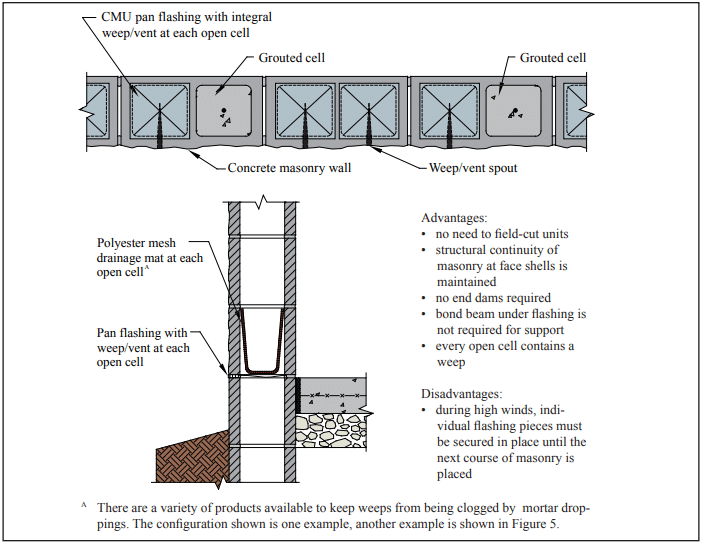

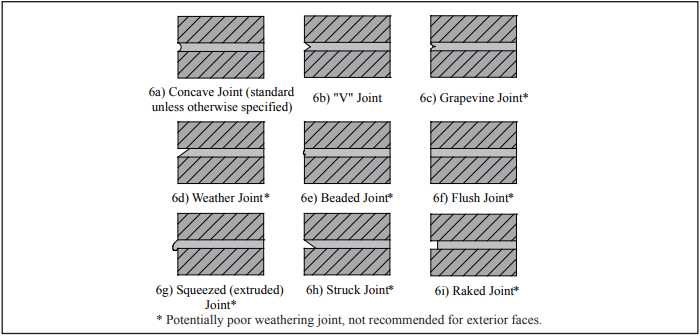

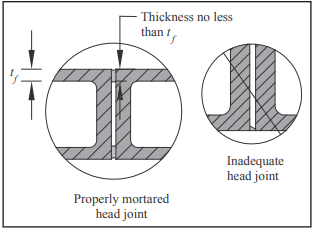

Other recommended practices involve the use of tooled concave mortar joints to reduce water penetration through the mortar joints. Masons should be careful to ensure that mortar dropped onto the flashing is minimized. This can be accomplished by beveling the mortar on the face shells adjacent to the cavities in cavity wall construction. In addition, cavity drainage mats, gravel beds, screens, or trapezoidal drainage material (filter paper) can be used to prevent mortar droppings from collecting on the flashing, which can form dams and block weep holes. Mortar collection devices at regular intervals or filling the cells with loose fill insulation a few courses at a time as the wall is laid-up, can be effective in dispersing minor mortar droppings enough to prevent clogging.

Weep holes, the inseparable companion to flashings, should provide free movement of water out of the concrete masonry cores, collar joints, or cavities. Any construction practice that allows forming the weep holes without inhibiting water flow may be used. Cotton sash cords and partially open head joints are the most common types of weep holes. Cotton sash cords should be removed prior to putting the wall into service to provide maximum unobstructed drainage. If necessary, insects can be thwarted by inserting stainless steel wool into the openings or using plastic or metal vents.

Vents

Weep holes often serve a dual function, first for water drainage and second as vents. Vents are desirable in some masonry wall systems to help reduce the moisture content of the masonry during drying periods. Air circulation through the cores and cavities within the masonry promotes equalization of moisture content throughout the masonry. Vents are considered desirable where air is confined within masonry, such as in parapets or areas of high humidity such as natatoriums.

MAINTENANCE

Maintenance programs should involve preserving the “as-built” design documents, records pertaining to inspections during the life of the structure, and continuing appraisal of the performance of the structure in addition to conventional repair and upkeep. Documentation of inspections, if efflorescence and water stains are observed, and logs of reported water penetration and their identified location, assist in determining proper corrective actions. Pictures with imprinted dates are suggested.

Knowledge of the wall design and construction can influence repair decisions. If flashing and weep holes were omitted during construction, it may prove effective to simply drill weep holes and vents to promote drainage and drying. Weep holes so drilled should be either at the intersection of the bed and head joints or into the cores at the bottom of the wall. Vents should be installed at the top of the wall or directly below bond beams. See TEK 08-01A Maintenance of Concrete Masonry Walls (ref. 4) for more detailed information on maintenance of concrete masonry walls.

When considering maintenance options, it is important to ensure that a masonry wall’s moisture control measures are kept intact. Thus, applying sealant beads, pargings, or coatings to a wall should be carefully weighed. Weep holes and vents should be maintained in an open condition to allow evacuation of moisture.

SUMMARY

Flashings are essential at foundations, bond beams, above and below openings, at shelf angles and at copings. Weep holes and vents reduce the moisture content of masonry walls. Proper selection of flashing materials, proper detailing, and proper installation will help ensure satisfactory performance.

REFERENCES

- The Building Envelope: Solutions to Problems, Proceedings from a national seminar series sponsored by Simpson Gumpertz & Heger Inc., 1993.

- Design for Dry Single-Wythe Concrete Masonry Walls, TEK 19-02B, Concrete Masonry & Hardscapes Association, 2012.

- Flashing Details for Concrete Masonry Walls, TEK 19-05A, Concrete Masonry & Hardscapes Association, 2008.

- Maintenance of Concrete Masonry Walls, TEK 08-01A, Concrete Masonry & Hardscapes Association, 2004.

- Standard Specification for Solder Metal, ASTM B 32-04, ASTM International, 2004.

- Standard Specification for Stainless and Heat-Resisting Chromium-Nickel Steel Plate, Sheet, and Strip, ASTM A 167-99(2004), ASTM International, 2004.

- Through-Wall Flashing, Engineering and Research Digest No. 654, Brick Industry Association.

- Water Repellents for Concrete Masonry Walls, TEK 19-01, Concrete Masonry & Hardscapes Association, 2006.